The home of the Euro Stoxx 50 and Bund Futures

Make Europe Great Again, Deutsche Boerse and Europe's biggest futures contracts

Exactly 20 years ago I was a sell-side equity research analyst covering a dozen European financial stocks but there was one stock investors wanted to discuss: Deutsche Boerse. Hedge fund manager Chris Hohn had just led an activist campaign to replace the Deutsche Boerse CEO who called it “Invasion of the Locusts.”!

Deutsche Boerse became a cult stock. The engine of the equity story was the Euro Stoxx 50. But after the Global Financial Crisis, it went to sleep just like Europe. Now Europe is back and so is Deutsche Boerse!

In this piece I go down memory lane of what made Deutsche Boerse a cult stock, what happened in between, and where we are now.

The Hedge Fund Hotel

Hedge fund crowded trades are in the news these days, whether it is the "magnificent 7” or the highly leveraged US Treasury basis trade. But this is not a new phenomenon. During the pre-2008 years, one of the most crowded hedge fund trades in European equities was Deutsche Boerse.

Why was it compelling?

It ticked a lot of boxes.

low valuation relative to US peers, even adjusted for growth,

an industry with massive scale economics that was consolidating.

the growth of capital markets, and specifically European capital markets.

the growth of derivatives markets,

the growth of the customer base - hedge funds, high-frequency trading firms, corporates hedging,

a sleepy management team without cost discipline, and slow capital returns (buybacks and dividends) which activists could attack.

Deutsche Boerse was and still is a very German company and German management team. But within the space of a few years, most of its shares were owned in Mayfair, Boston, and NYC. Chris Hohn’s TCI owned around 10% of shares but there was another hedge fund that was just as large but a firm that is now ancient history. The event-driven hedge fund Atticus (which closed in 2009 following huge losses) also held 10% of the shares of Deutsche Boerse. A series of other very large equity long/short hedge funds including 2 of the most famous Tiger Cubs together owned another 30% of the company.

The Deutsche Boerse story also attracted some of the largest US institutional investors for the same reasons. At one point more than half of Deutsche Boerse shares were owned by investors based in the US and another quarter by investors based in London.

When I went on the morning call/meeting in London with the equity salesforce to push the stock, interest was mixed, with most traditional European and UK investors less interested in the story. But my marketing trips to the US became more and more packed. Sometimes a dozen meetings in a day. Large group meetings for smaller clients. No US marketing trip was complete until I got off the red-eye back to London, and ran to Mayfair to update investors about what the big East Coast activists were saying on the stock!

In short, Deutsche Boerse was a hot stock. My description may make you think, these were the clients of the investment bank I had worked for. In reality, many of these large long-term hedge funds didn’t trade frequently and had concentrated books including billion-dollar positions. They were not large clients of sell-side research departments, in the way the “pod shops” are.

Deutsche Boerse’s share price went up by sixfold in the years before the Global Financial Crisis and then lost two-thirds of its value in the crisis. It made fortunes for those hedge fund investors but part of the selloff was also driven by the hedge fund hotel getting hit by their own margin calls/investor redemptions.

The Euro Stoxx 50 - the S&P Future of Europe

The rally in European share prices in the years ahead of the Global Financial Crisis was strong and faster than US markets. But the other trend was the market had moved Pan-European. In the mid to late nineties there were still as many country analysts covering European equities but with everything centralized in London, the market went Pan-European. The increased presence of US institutional investors in European equities was part of the story. As was the rapid growth in the equity long/short hedge fund industry in New York and London. When Americans got up before dawn they wanted to trade the whole European continent and country risk didn’t matter as much.

These were the tailwinds behind the emergence of what is still today one of Deutsche’s Boerse flagship derivatives contracts, the Euro Stoxx 50. Until then Deutsche’s Boerse futures exchange Eurex had largely been known as the exchange that took the Bund future back to Germany from Liffe in London.

The percentage of Eurex’s revenues that came from equity index contracts rose from 20-25% in 2000 to 45-50% by 2007. The percentage of Eurex’s equity index volumes that came from the flagship Pan-European contract the Euro Stoxx 50 rose from less than 15% in 1999 and 30% in 2000 to more than 75% in 2006 and 2007. Investor demand to trade country indexes across European countries was much weaker as the chart below illustrates.

Eurex was around 30% of Deutsche Boerse’s revenues and 35-40% of group profits in the years just before the Global Financial Crisis. But it was the fastest growing business, with the deepest barriers to entry. A trophy asset trading, which was valued at a fraction of US peers like CME and ICE in any implied sum of the parts valuation (the rest of Deutsche Boerse’s profits at the time were generated from the DTCC/Euroclear like custody business Clearstream and to a lesser extent the German cash equities exchange).

The years of wilderness

The sovereign crisis of 2011 re-introduced country risk across Europe. The most obvious impact was on the importance of Bund Futures as spreads between different European sovereign debt, started to blow out.

The fifteen years of stock market underperformance, slower economic growth, and financial de-leveraging relative to the US also had ramifications for the growth of Deutsche Boerse’s equity index complex.

The S&P500 managed to get back to its 2007 highs by the start of 2013 and increased fourfold from there. The Euro Stoxx 50 index only managed to claw its way back to its 2007 highs early in 2024 and is still only up 20% over 18 years.

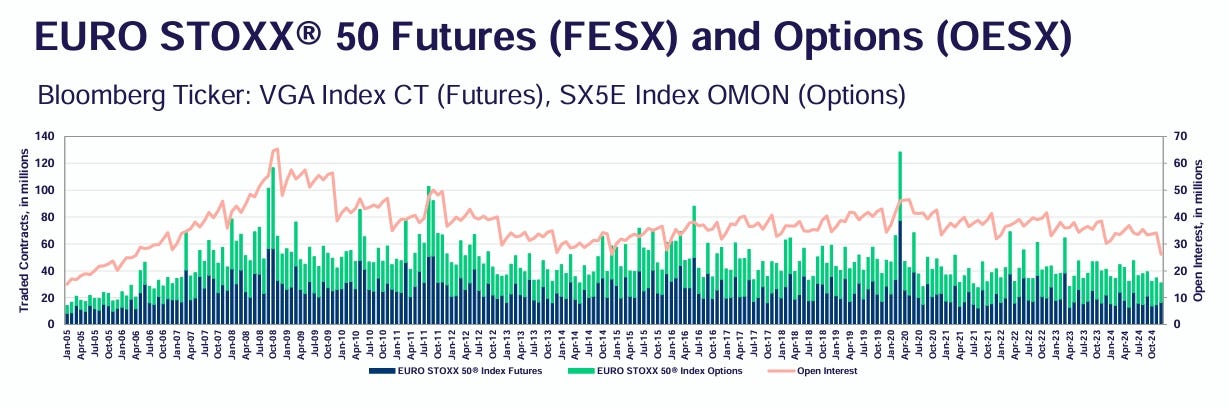

Euro Stoxx trading volumes have not done much better. Europe was dead so it is not completely surprising. Trading volumes in the chart below in blue (futures) and green (options) show flat to declining absolute levels of activity since 2007. Open interest is the total number of futures and options contracts held by market participants at the end of the trading day. It is used as an indicator to determine market sentiment and the strength behind price trends. Here the red line shows an even more stark trend with open interest of just over 25 million contracts in 2024 versus a peak of 60 million contracts in 2008 and 40 million contracts in mid-2007.

CME equity futures trading volumes are distorted by changes in contract sizes but looking at the revenues of CME’s equity index complex (which is 75% from S&P futures) there has been a 2.5x increase over this period and a 2x increase in revenues over the last decade. CME’s equity index derivatives revenues are today more than 2x the size of Eurex’s equity index revenues illustrating the diverging growth in the relative capital markets.

Europe is back

The Bank of America fund manager survey this week highlighted a record swing in investor sentiment from US equities into European equities. Of course, share prices were already telling us this with declines this year of 4% and 8% respectively for the S&P 500 and Nasdaq Composite and the DAX30 roaring up 16%.

The Euro Stoxx 50 is up 12% so far this year. Could it be the next Magnificant 7 or FANG? Probably not but let’s look at its current index constituents and their relative weighting. Remember this only covers the Eurozone and not all companies in Europe. The largest weighting currently is ASML at 8.5% of the Index and the other tech name is SAP at just over 4%. The big luxury/consumer names (LVMH, L’Oreal, and Hermes) are high up as are manufacturers like Siemens, Schneider Electric, and Airbus.

Deutsche Boerse is also now in the Euro Stoxx. It took more than a decade for the company’s share price to recover its 2007 highs but the share price has almost trebled in the last 3 years and is up almost 50% in the last year. It benefited massively from ECB interest rate increases given that almost 20% of revenues come from treasury income (mostly at Clearstream). Much of this will unwind this year given recent rate cuts. But Bund futures volumes which generated just under 10% of revenues last year have gone ballistic this year given the sharp market moves.

Deutsche Boerse has diversified in the last decade. The fastest organic growth within this has come from the EEX (European Energy Exchange) in power and natural gas trading. There have been numerous acquisitions of which the largest is Blackrock Aladdin competitor SimCorp. Given the years in the wilderness, the equity index has shrunk materially as a percentage of the group. Last year Euro Stoxx futures and options 50 are likely to have been around 5% of group revenues. Hence it is less a geared play on the recovery of this specific Pan-European Index contract.

Given the geopolitical uncertainty and the German fiscal stimulus, Eurex at least in the short-term will be known for the Bund Future and not the Euro Stoxx 50. Volumes in the latter have not surged in the same way. But if European exceptionalism does ever return who knows?