It’s exactly 25 years on from the bursting of the dot com bubble. I was doing TMT equity research at Frank Quattrone’s CS First Boston at the time. There is no doubt that the bubble was owing to the excitement around the emergence of the Internet but most of the memories focus on tech, not telecoms.

The telecoms bubble was big. It was just as big as the tech bubble. It was more global. There may not have been as many IPOs as tech, but the overall fees paid to investment banks in telecoms deals were just as large.

Tech came back. But telecoms never really did.

Let’s dig in.

The US telecoms bubble

As with the Global Financial Crisis a few years later, deregulation played its part in the telecoms bubble of the late nineties. In early 1996, the Telecommunications Act was signed into law in the US. This aimed to reduce barriers to entry and allow more competition between regional telecom operators, local and long-distance telcos, and across different market segments like voice and data. This combined with technology improvements in fiber-optic cables and the growing demand for new Internet, mobile, and broadband services led to a capex binge similar to what we are seeing with AI today, once adjusting for inflation.

This was a built it and they will come era. A Wired Magazine article on dot com telco darling Qwest in 1998 said: “Qwest is operating under an if-you-build-it-they-will-come vision. Bandwidth restrictions, the company believes, have held back development, of all manner of innovation. Now the prospect of virtually endless throughput will free up the planet for a host of new applications in such areas as high-speed video and multimedia.”

According to the Richmond Fed paper Boom and Bust in Telecommunications investment in communications equipment using constant 1996 dollars grew from $62 billion per annum at the start of 1996 to over $135 billion per annum by the end of 2000. Real investment in telecoms structures was relatively flat for most of the nineties but rose 75% in 1999 and fell back to levels seen a decade prior by the end of 2002. Employment in the telecoms sector declined by 22% from the peak and profits of more than $20 billion per annum in 1995 and 1996 became losses of a similar amount in 2000 and 2001.

The consumption rate of US telecoms grew at 7.4% per annum between 1996 and 2001 but this was only marginally higher than the 6.7% growth rate in the 1990 to 1995 period. The hype circulated by CEOs of telcos such as Worldcom and Bellsouth during the boom years was that Internet traffic was doubling every three to four months when in fact it was doubling every year. cause of telecom crash

The prices for long-distance calls and wireless fell by 18.5% and 32% respectively between 1997 and 2003 but the price of local fixed-line calls rose 22.7% during the period. At the same time, there were large advancements in the capacity of fiber cables that allowed massive increases in data throughput, and it was not just the telecom firms but also equipment providers that benefited.

How big was the US telecoms sector at the peak?

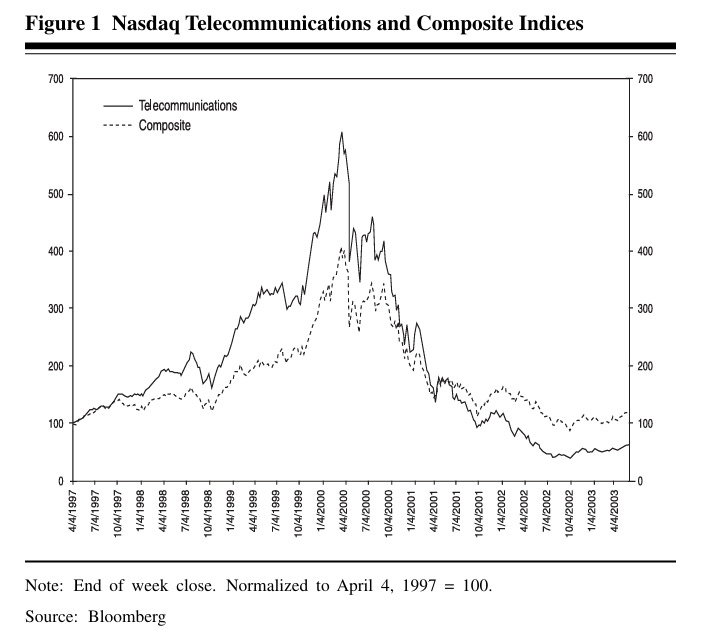

The above chart from the Richmond Federal Reserve paper illustrates that the increase and decline in the US telecoms sector share prices were greater than that of the broader Nasdaq composite index. In the three years to the March 2000 peak, the former rose at a CAGR of 84% ahead of 61% for the latter. Similarly, in the three years after the peak telecoms share price declined by a CAGR of 50% a pace faster than the 32% annual decline in the Nasdaq composite. The US telecoms operator sector lost around $700 billion in value in two years.

The largest player in this trillion-dollar sector just after the bubble started to burst in Q2 2000 was AT&T with a market capitalization of around $160 billion. A few hundred billion dollars of market capitalization was in the Bell baby regional telcos (SBC, Bell Atlantic, Bellsouth, US West) that had been spun out of AT&T over a decade earlier owing to anti-trust requirements.

But the extravagance and indebtedness of the time was best characterized by Worldcom, which was the second largest long-distance telecoms operator in the US after AT&T. It grew much faster through multiple acquisitions including the much larger MCI in 1998. By the time the dot com bubble started to burst Worldcom was handling half of all Internet and email traffic in the US. But as the telecoms industry was hit by the oversupply glut and the impact of macro-economic weakness on demand the company continued to guide Wall Street towards double-digit growth by inflating earnings. Eventually, earnings and the share price tanked. By the time a huge accounting fraud was uncovered in 2002, the company’s debt was already junk and it was forced into bankruptcy and CEO Bernie Ebbers ended up in jail a few years later.

The period was also characterized by startup telcos like Global Crossing and Level 3 Communications that reached valuations of tens of billions of dollars. The former was founded in 1997 and focused on developing major subsea cable systems. It was worth around $50 billion within two years and would file for bankruptcy in 2002. The latter just about survived owing to its cash pile but having also reached a market capitalization of nearly $50 billion at the top, Level 3’s share price fell 95%.

The share prices of telecom operators during the time understate how much of the Nasdaq bubble was owing to this capex binge and the excess supply of bandwidth. Real things were being built but analogous to the British railway bubble of the 1840s or US railway bubbles later in the nineteenth century it took years to work through excess capacity and retail investors took a lot of pain in the meantime. Cisco Systems, which manufactured key equipment like switches and routers that were needed for the Internet did grow revenues at 55% in 2000. This was slower than the 75% CAGR for the prior decade but very impressive given the law of large numbers. However, this lagged its share price, which increased eightfold between 1997 and 2000 briefly overtaking Microsoft to have the largest stock market capitalization at $575 billion. A similar story could be found with telecom equipment makers like Lucent Technologies and Nortel Networks, which were among the most valuable companies in the world.

A global story

More so than the tech boom of recent years or the Internet side of the late nineties dot com bubble, the telecoms bubble was truly global.

In Europe, in the absence of large tech firms, the telecoms sector became the proxy for all the Internet fervour. A key moment was the 1996 Deutsche Telekom IPO, which at the time was the largest IPO ever. At the height of the bubble in 2000, Europe’s largest telecoms operator had a market capitalization of well over $200 billion and was worth more than any of its US peers. Moreover, the ten largest European telecoms operators were also together worth more than their US peers. These included national carriers across major European countries. Just like their US peers, European telcos went on a spending binge upgrading networks. This included tens of billions of dollars paid by telcos to European governments in auctions of 3G spectrum licenses.

Much has been written about the lack of tech stocks in the FTSE100 nowadays but the biggest difference with the dot com bubble is the performance of the telecoms sector. At the peak of the dot com bubble, Vodafone was the most valuable stock in the FTSE100 with a market capitalization of around $350 billion. Within two years this had fallen by 75%. After a brief recovery they have struggled in the last decade and today Vodafone is worth less than $25 billion. The national carrier of the UK, British Telecom saw its market capitalization peak at almost $150 billion in late 1999 and had fallen to $22 billion by 2003. Two decades later its market capitalization is $20 billion. The UK also had smaller players like Cable and Wireless and Colt Telecom get hit and having refocused itself on telco equipment Marconi lost almost $50 billion of stock market value.

Just like the US, the equipment manufacturers were also a significant part of the telecoms bubble in Europe. Nokia was one of the most liquid stocks in Europe and had a market capitalization of well over $200 billion at one stage. Ericsson was a little smaller than Nokia. There was also Alcatel in France.

Although Europe was the largest of the telecom regions, the largest individual telecoms operator globally in the late nineties was the Japanese state-backed carrier NTT and its mobile operation DoCoMo with stock market values of around $300 billion. Other parts of the world had smaller players such as $90 billion China Telecom, $70 billion Telstra in Australia, $50 billion Korea Telecom, and others.

Tech or telecoms feeds Wall Street?

Deregulation fuelled the growth in the competitors in local telecoms markets in the US from 30 in 1996 to 711 in 2000. The increased demand for services also resulted in an increase in their revenues from less than $5 billion to $43 billion over the same period. This led to an IPO boom across the wider sector including McLeodUSA in 1996, Qwest Communications and Metromedia Fiber Networks in 1997 and Sprint PCS in 1999.

Unlike the small Internet companies, what made the telco IPO boom very profitable was a mixture of IPO fees, follow-on equity raises, loans, bond sales, and M&A fees. To secure key underwriters like Salomon Brothers with its infamous superstar telco research analyst Jack Grubman telcos paid very high fees. When Global Crossing was listed in 1998 (only a year after the company was founded) it only raised $400 million but Salomon Brothers and Merrill Lynch took fees of over 7%. But this was a tiny fraction of the business Global Crossing gave Wall Street over a short number of years to raise equity, M&A deals such as the ten billion dollars plus Frontier Corp purchase, and a huge amount of debt in the form of loans, convertibles, and junk bond sales. In total Wall Street investment bankers earned more than $400 million in fees from Global Crossing during the telecom boom and bust.

During the boom years, the telco IPO market may not have been as hot as the tech sector, but more was being raised in telco debt offerings than equity raises. As well as the capex binge, deregulation, and rising share prices kicked off a telco M&A binge. The telecom sector’s share of high-yield debt issues grew from 15% in 1997 to almost half of the whole market by 2000. US telcos raised more than a half trillion dollars of debt in those boom years.

According to Thomson Financial data, Salomon Brothers earned more than a billion dollars in investment banking fees during that time. No wonder Jack Grubman was paid $20 million in 1999 matching top Internet analysts Mary Meeker and Henry Blodget. The US telco IPO boom lasted until AT&T Wireless raised $10.6 billion in April 2000, a deal that Salomon Brothers earned more than $60 million on and also created a legendary story of whether CEO Sandy Weill had influenced Grubman’s stock rating on AT&T.

The telco IPO boom was a global phenomenon. Internationally, the key theme was the privatization of formerly state-owned monopolies. In 1997 as well as the record $13 billion fund-raise by Deutsche Telekom, there was more than $7 billion raised by the France Telecom IPO. The strong share price performance gave France Telecom a peak market capitalization of more than $175 billion and created an insatiable investor appetite for similar IPOs. In 1997 China Mobile raised $4 billion and Australia’s Telstra raised more than $5.5 billion. The following year Swisscom raised more than $7 billion.

In the US Salomon Brothers may have been the clear leader in telecoms investment banking ahead of Merrill Lynch but internationally Goldman Sachs was a major player leading a large number of European privatizations like Deutsche Telekom and the landmark NTT DoCoMo IPO in 1998. But by 2000 IPOs of international telcos like Telekom Austria, Telefonica’s mobile business and Norway’s Telenor were also struggling.

Goldman Sachs was also the M&A banker of choice for highly acquisitive Vodafone. Sir Chris Gent may not be remembered as a major part of the dot com era but as Vodafone CEO he doubled the size of his company with the $58 billion acquisition of AirTouch in 1998 following a bidding war against Bell Atlantic. He also timed the top of the bubble with the record-breaking $190 billion hostile takeover of Germany’s Mannesmann in early 2000. The Goldman Sachs senior partner who advised Gent, Scott Mead retired from banking in 2003 having made a fortune. He is nowadays a photographer, a pretty good one!

25 years on from the burst of the telecoms bubble and tech is back but it is unlikely we will see another telecoms bubble. Market capitalizations, valuations, and investment fees of the telco sector are now a fraction of the size of the technology sector.

I came to that sector a while later in the mid-2ks, during the post bubble cleanup and in time for the Dawn of Mobile Internet!!

The depressing thing really was that the Eurotelcos borrowed all the money and used it to build empires, not networks. They put an enormous amount of effort into avoiding building out FTTH as far as possible, treated all things Internet as a weird American perversion as late as they possibly could, but boy howdy they stuck some flags in maps and threw money at TV people.

TEF was perhaps the most ridiculous; I vividly remember going to their comically enormous postmodernist-Alhambra fusion HQ in the great Spanish bugger-all and looking at the gallery of founding father portraits while the company was ~€80bn in debt and putting a giant neon blue lightbulb in its London office to be more Digital. The portraits reminded me a bit of this Goya: https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/objects/47183

On the other hand, Level(3) or should I say...AS3356...is still a top name for Internet backbone today everywhere in the world even if it is a Centurylink division these days.

Later on, of course, Verizon and T-Mo USA discovered the joy of pure Internet while AT&T got hooked on the telco-as-media crack and Sprint did...whatever the hell Dan Hesse was up to while he was the best paid CEO in the business while the company fell apart.

Top summary.

But with Ai, ‘This time it’s different’ 🤣